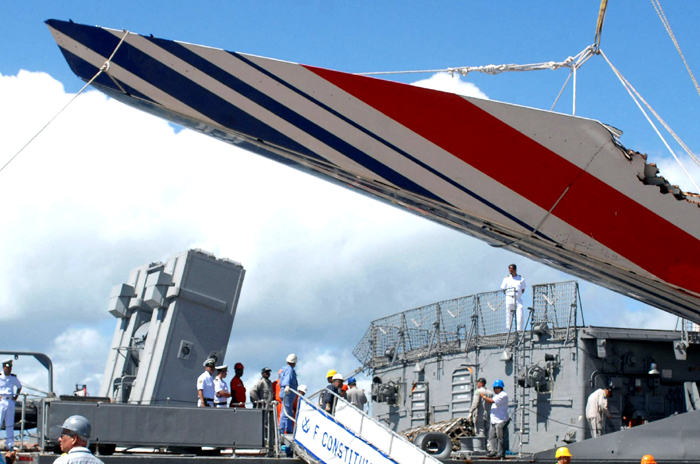

PARIS – A French criminal court began the historic manslaughter trial of Air France and planemaker Airbus on Monday.Relatives of the people who died when an A330 passenger jet crashed into the Atlantic and killed everyone on board 13 years ago are demanding justice.

The heads of both companies stood silently in front of a judge in Paris as the names of all 228 people who died when AF447 disappeared during a nighttime equatorial storm on June 1, 2009, while flying from Rio de Janeiro to Paris were read.

After a series of legal setbacks, families from some of the 33 countries on board, mostly from France, Brazil, and Germany, crowded into the Paris Criminal Court.

Related: Amid inflation, Air France will pay bonuses and raise wages.

“We’ve been waiting for this day for 13 years, and we’ve been getting ready for a long time,” said Daniele Lamy, who lost her son in the worst accident for the French national airline.

After using remote submarines to look for the A330’s black boxes for two years, investigators found that the pilots handled a problem with iced-up speed sensors badly and lurched the plane into a freefall without responding to “stall” warnings.

But France’s BEA accident agency also showed that Air France and Airbus had talked before about how reliable the probes were. It also made dozens of safety recommendations about everything from the design of the cockpit to training and search-and-rescue.

Experts say that the most important part of the trial will be figuring out how much the pilot or the sensors were to blame. This will show a fight that has split France’s aeronautical elite.

Airbus says the crash was caused by a mistake by the pilots, while the flag carrier says the pilots were overwhelmed by confusing alarms.

Lawyers warned that the long-awaited trial, which is going on now because a decision to drop the case was overturned, shouldn’t leave out family members who were there on the first day.

“In this trial, the people who were hurt must stay at the centre of the discussion. “We don’t want Airbus or Air France to turn this trial into a meeting of engineers,” said lawyer Sebastien Busy.

After an aeroplane crash, this is the first time that French companies are being tried for “involuntary manslaughter.” The families of the victims say that each manager should also be on trial.

Relatives also didn’t care about the fact that each company could be fined up to 225,000 euros ($220,612), which is equal to just two minutes of Airbus’s pre-COVID revenue or five minutes of the airline’s passenger revenue. Larger amounts have also been paid out in compensation or settlements that haven’t been made public.

“They won’t be worried about the 225,000 euros. “What’s at stake for (Air France and Airbus) is their reputations.” Alain Jakubowicz, a lawyer for families, said this.

“For us, it’s about something else: the truth and making sure that people learn from all of these terrible events. “This trial is about bringing back a human touch,” he told the news people.

The CEOs of Airbus, Guillaume Faury, and Air France, Anne Rigail, sat down just before the trial began. It will go on until December 8.

Family members were helped by people who had been trained to help accident victims while translators gave out headsets.

PILOT TRAINING

AF447 caused people to rethink training and technology, and it is seen as one of a small number of accidents that changed aviation. For example, the way the industry handles loss of control changed because of a few of these accidents.

The big question is why the three pilots, who had more than 20,000 hours of flying experience between them, didn’t realise that their modern jet had lost lift, or “stalled.”

To do that, they had to push the nose down instead of pulling it up, which is what they did for most of the fatal four-minute fall toward the Atlantic in an area without radar.

Related: Air France-KLM reduces its forecast due to “operational issues”

France’s BEA said that the crew didn’t handle the icing problem correctly and also didn’t have the training they needed to fly manually at a high altitude when the autopilot failed.

It also showed that the signals from a display called the “flight director” were not always the same. The flight director has since been changed to turn itself off in such situations to avoid confusion.

Before the trial, neither company said anything.

(This story has been resubmitted because of a mistake in paragraph 16).